Corona is neither simply juxtaposed to nor simply superposed over COVID-19. In a way, Corona substitutes itself to COVID-19, in another way Corona uses and transforms COVID-19 to realize a synthesis of a higher order.

The above is a translation of the best two sentences about culture and humanity ever written by an anthropologists. In the original Lévi-Strauss ([1949] 1969: 4)) possibly meant it optimistically (Boon 1982: Chapter 4). Translated into the Corona epoch, it may or may not be so. In any event it is essential for an anthropologist to keep the virus (that is the material and biological — C19 here) distinct from the human response (that is the social and cultural—Corona here). The response to C19 produced a “synthesis of a higher order,” Corona that has caught about all 7.8 billion human beings on the planet. For the million and a half who have been identified as carrying the virus, for their kin, and for those who treated them, C19 may be a matter of direct experience. For everybody else, what is experienced is Corona in the reports by the media, in the regulations by government, in conversations among kin, friends, colleagues. As an individual, I am lucky that noone in my first degree network has experienced C19. But we all have experienced, and continue to experience, Corona.

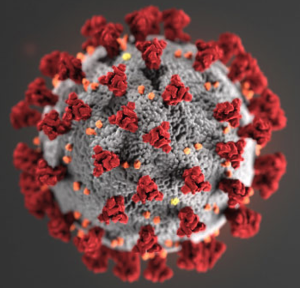

In an earlier post (March 28, 2020) I wrote that C19 might kill you and but it cannot close a restaurant. That is, and against some who wrote that illness is a metaphor (Sontag 1977), C19 is a “thing with agency” (in Latour’s sense). Actually it is a thing that is alive and will change as human responses begin affecting it (through vaccines, etc.). The naming of the virus “Crown,” in Latin, by whomever is, of course, a metaphor based on its appearance under an electron microscope.

C19 is not a metaphor though it will remain something about which metaphor will be made—along with much else in discourse, through speech acts and other means that will much more consequential than metaphors.

The anthropological response to Corona will have to focus minimally on two aspects of the human response: how do humans get to “see” C19 and act directly on it. Most humans will never see it or act on it except for the few whom we can gloss as “scientists.” They will work mightily on that front. Anthropologists of science may or may not be helpful there. Where anthropologists will be useful is in the analysis of the spread of Corona, its consequences, and its evolution as it will morph given what will have been done earlier, and what was done elsewhere.

Consider: on April 6, as I write this, Euro-America is days into “isolation” and “social distancing.” When the regulations for this started depends on the nation-state under which one lives. Similarly, the exact nature of these regulations and their enforcement vary here and there, even though all governors (that is those involved in making the regulations) know what others are doing. In the US itself, resistance can take many public forms: compare the Hasidic in Queens to sheriffs in Idaho

In France, for example, all are required not to move more than 3/4 mile from their house and hand the police, when asked, a written, signed, document explaining why they are out. In New York City, one can still walk or drive to a grocery store or park. In France one can be fined and even arrested for transgressing the boundaries. In New York the policy will break groups of people larger than a few. There are now reports about some governors discussing what will be the modalities of de-distancing. One can be sure that these discussions will be acrimonious, with much disagreement, and that they will produce different measures here rather than there.

In other words, as with everything else that resist human beings, human beings will make culture and will live with what they have made. That is they will make some (many) things that will materially resist them. When Lévi-Strauss wrote about “synthesis of a higher order,” he was not writing about “interpretations” that live solely in the imagination. The synthesis is not a psychological event (though it may have psychological consequences) it is a social one. It takes shape in interaction, through conversation, instruction, punishment if necessary.

The challenge, in the anthropological study of Corona, will consist in figuring out who, in any particular place and at any particular moment, is involved in producing what aspect of Corona. To take the one example of the closing of a restaurant in a ski resort of Wyoming, one would need to trace the acts of the restaurant managers and the consequences for the managers and employees. To take another example, on March 28, I was told by the desk person at my hotel that I had either to leave or stay in my room for 30 days starting on March 30th. I did not investigate whether this was an accurate translation of the town council resolution, nor was I present when the regulation was passed down to the hotel. But, on the basis of the statement, I decided to leave the following day.

Many anthropologists might be interested in “why” I took this decision (or “why” is was in Jackson, Wyoming, of all places). They might look into my early childhood, into my personality or character, or into my identity. Some might emphasized that I had a good car, and that I was healthy enough to make the 4 days trip back to New York. Some might wonder why I decided to go back to New York at a time when everyone was being told that things were terrible there.

All that may be interesting if you are concerned with me. However, as an anthropologists, I am concerned with particular conditions that others make for me in my peculiar conditions.

That is the problem on which cultural anthropologists must continue to work.

References

Boon, James 1982 Other tribes, other scribes: Symbolic anthropology in the comparative study of cultures, histories, religions, and texts.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lévi-strauss, Claude [1949] 1969 The elementary structures of kinship. Tr. by J. Bell and J. von Sturmer. Boston: Beacon Press.

Sontag, Susan 1978 Illness as metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[print_link]