Balzac was one of the first writers to make bureaucracy the subject of serious fiction, notably …, where he takes the un-Kafkaesque delight in its lumbering procedures. As he shows in these bureaucratic dramas which are still enlightening today, the monster was not so much malevolent as driven by almost random interference by its futile overactivity. (Robb 1994: 106)

As I like to say, only human beings can close, and then reopen, restaurants. So far I have mostly pointed at “governors” as the humans who act. One does not have to read much Latour to realize that this sketches a reality in much too broad a stroke. In real life, governors may order restaurants closed but the one person who will tell the manager that she must close her restaurant is probably a very minor employee of a local health administration. As I told it in March 2020, my first direct encounter with the virus-as-humanized was in a busy diner, by an interstate highway somewhere in North Dakota, when I witnessed an overly self-satisfied lady telling another lady and her staff around her that the county officials might order her to close the diner following orders from higher officials. Bourdieu reminded all of us, anthropologists, to note marks of distinction. And so I admired the distinction between the well dressed, coiffed, fed official who was not losing her job, and the harassed, not so well-dressed manager, server, cook who were going to lose theirs.

As usual, I am not saying anything as to whether restaurants should have been closed (or re-opened). What I am doing is pursuing the theme I introduced in my last post about “governmentality” as a label for something anthropologists must now take into account anywhere in the world, and as a dangerous concept if it leads to gross generalizations. “The State made me do it” is not an analysis even when the State, that is some governor, set the stage (animated it, directed it, etc.) for whatever everyday encounter an anthropologist may be “participantly observing.”

What I am proposing, and suggesting to the students in their quest for research topics, is a more determined investigation of “speech acts” as they reverberate, as well as the emergence of alternate governors as a major speech act does reverberate.

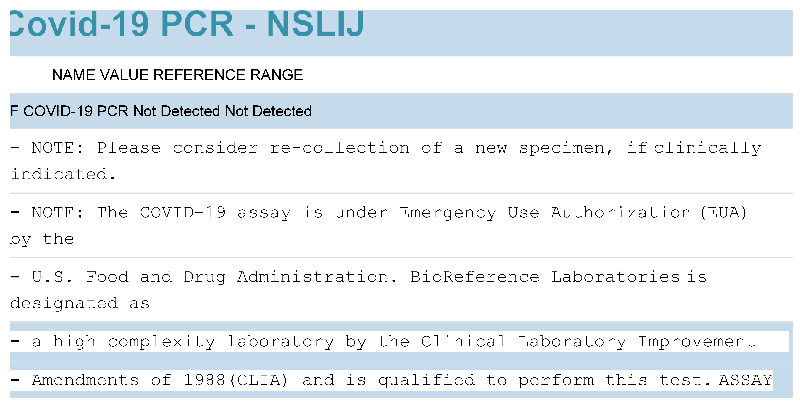

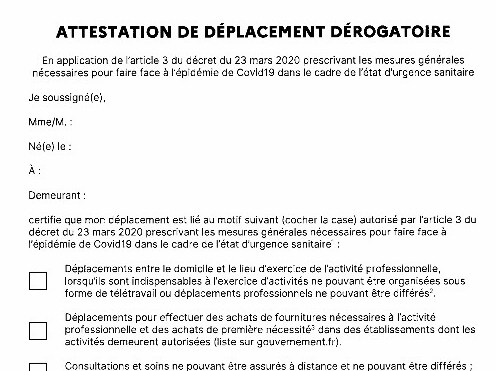

“Speech act theory” was a major advance in sociolinguistics, and in fact in all the social sciences as it emphasizes that about all human activity proceeds through speaking and not simply through symbolizing, classifying, imagining. Language is also the main tool through which some people get some other people to do what must/may (or must/may not) be done—or at least try to get them to (not) do it. However, the statement by a governor (president of a country, or university) “Get vaccinated, or else” is, ethnographically, an Ur-statement . It is the first in what can be a very long chain of such statements. Even so, it must must have occurred within an interaction between the Over-governor and some subordinate. Anthropologists can only very rarely be allowed to observe such interactions but we can imagine that this statement actually had the form “tell the minister to tell the under-minister to tell” ….. an employee in some Human Resources to e-mail other employees to “get vaccinated or else” and then to report to her supervisor that she had accomplished the task (who then reported it back to her supervisor…).

This chain may be what the word “bureaucracy” indexes but, noticing this chain as chain opens all sorts of possible investigation about the many ways that chain might be broken, or by passed, or produce ever more complex sub-mandates (as happens in France as some middle governors get to specify categories, exceptions, etc.). The media of course is an alternate chain that partially short-circuits the bureaucracy so that the last human in the bureaucratic chain (say, the HR employee) may never have to utter the order: the employee may already have complied for whatever reason—or have initiated a protest.

But there are other chains.

I have been in a small village in Southern France for the past few weeks. Here, as probably everywhere else in the world, the politics of “Covid” (what I refer as the “Corona” epoch) are a major topic of conversation both idle (“do you know what ‘they’ said?!!”) and consequential (“how do I get that pass?”). In the village, and to my surprise, at least half of the people I met asserted with vigor that they were not vaccinated, did not want to get vaccinated, and were going to resist the latest order from the over-governor of France. Many of the non-vaccinators were “young” but I met one lady well into her 70s who was not going to get vaccinated even as her husband, standing by her, said he had been. One can imagine the conversations between the two… A vaccinated of the same generation told that he would not have gotten vaccinated if his daughter-in-law had not acted as a local governor and speech-acted: “Get vaccinated or get banned from family reunions.” One can also imagine the conversations between grand-father, son and daughter-in-law (and probably many more in the kin group)! As I also like to teach local “communities of practice” are not only cozy settings for learning but also fraught settings for political conflict and domination.

In other words I imagine (not to say “I hypothesize”) that local conversations that lead to (not) getting vaccinated parallel the conversations that led the President of France (or the Mayor of New York City as of August 4, 2021) to mandate showing a pass to enter various settings. The President or Mayor, with their police powers, certainly have more power than daughters-in-law. But the power of daughters-in-law (or the lack of power of a son/husband) cannot be underestimated.

Thus the chain from Over-governors to local enactments is “fractal” in the sense that, in any setting, the relationship between however local a governor and their subordinate is going to be the trigger of a chain of sub-mandates each of which susceptible to being expanded or resisted in imaginative ways the initial governor could not … imagine. This model of bureaucratic “overactivity” will have to be merged with Lave’s model of movement through social structural positions also must involve such speech acts as a “full” member tell another (possibly not so full member…) “let this person work in our shop as an apprentice” and so that persons becomes, analytically, a “legitimate peripheral participant.”

References

Robb, Graham 1994 Balzac: a biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

[print_link]

The humans noticed her sticking blades of grass in her ears and this being adopted by other chimpanzees in the same sanctuary, and then passed on in further generations even after she died (Natalie Angier

The humans noticed her sticking blades of grass in her ears and this being adopted by other chimpanzees in the same sanctuary, and then passed on in further generations even after she died (Natalie Angier