The answer to that challenge will require a new level of political imagination — a combination of educational reforms and unprecedented collaboration between business, schools, universities and government to change how workers are trained and empowered to keep learning… America today desperately needs a center-right G.O.P. that is offering merit-based, market-based approaches to all these issues — and a willingness to meet the other side halfway. (Thomas L. Friedman. A version of this op-ed appeared in print on November 7, 2012, on page A27 of the New York edition with the headline: Hope And Change: Part Two. My emphasis)

Thomas Friedman thus concluded an opinion piece celebrating Obama’s re-election: Let Business, School & Government collaborate!

Nothing really new here. For close to two decades, the choir keeps singing the same hymn whether the director is Republican or Democrat. If ever there is a political consensus here, in government at least, this is it. And, as this consensus is getting translated into more and more detailed regulations down to the level of measuring the merit of individual teachers on an on-going basis, the consensus is getting less accessible to effective criticism. “Neo-liberalism,” as many of my students like to call it, is alive and very well. Actually it is thriving when the G.O.P. in the United States is criticized for not being open to “merit-based, market-based approaches”!

But what is this consensus all about, practically? Provocatively (I hope) this is about a re-invention of vocational education and it leads me to think about one moment in the history of the interplay between Business and School.

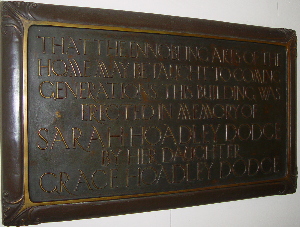

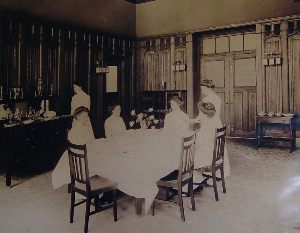

In the 1880s, Business (as represented by Miss Grace Hoadley Dodge) collaborated with School (as represented by the philosopher and future president of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler), to found was to become Teachers College. In the origin myth we tell, there was a disagreement between Dodge and Butler about the mission of the college, with Dodge pushing for what she imagined new workers might need in the coming 20th century. Her eponymous building is dedicated to teaching the “enobling arts of the home” and contains a “Tudor Room” that was the “Table Service Lab” “where exercises in table setting and meal service occurred.”

In the 1880s, Business (as represented by Miss Grace Hoadley Dodge) collaborated with School (as represented by the philosopher and future president of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler), to found was to become Teachers College. In the origin myth we tell, there was a disagreement between Dodge and Butler about the mission of the college, with Dodge pushing for what she imagined new workers might need in the coming 20th century. Her eponymous building is dedicated to teaching the “enobling arts of the home” and contains a “Tudor Room” that was the “Table Service Lab” “where exercises in table setting and meal service occurred.”

Butler successfully redirected Dodge’s efforts to the training of teachers. In effect, Butler, like most intellectuals and academicians to this day, separated the mission of schooling from the vocational training of the future work force. I am not sure who Butler imagined would train workers into the trades, but I suspect he expected the employers to do this, whether through apprenticeships or other means. “Education,” that is public schooling, was to be about democracy and the culturing of citizens (Dewey 1916). Government does not appear in this origin myth though much of justification for state funding of public schools did not emphasize what is now often called the building of “human capital.” By the end of the 19th century School had insulated itself from Business by encasing it into boards of trustees whose responsibilities were purely financial. Miss Dodge could fund Teachers College but she could not dictate curriculum.

Business did not give up, and Government got into the act. One hundred and thirty years after “Dodge vs. Butler” was settled in favor of Butler, a whole set of miscellaneous forces (donors, governments, students, parents) push colleges and universities to be ever more “practical” and, as Government uses its regulatory powers to enforce business requests, to demonstrate that their curricula are indeed practical in the training of workers. And so Teachers College, which still educates some teachers, survives by (vocationally) training young women (mostly, and still) to work in the expanding bureaucracies of “education” and related administrations—though perhaps not to an extent that would satisfy Thomas Friedman.

Now, when Lawrence Cremin taught me the history of American education, he spent some time tracing the evolution of colleges from seminaries, to finishing schools for the children of the elites, to tools of the state to improve agriculture (land grant universities) to the conduit through which fundamental knowledge was developed (on the German model) (Cremin 1980, 1988). As usually happens as cultures change, old practices do not disappear though they may get subsumed. Harvard still has a Divinity School; to this day the University of Chicago College still requires students to take “a total of six quarters in humanities and civilization studies”—thereby preserving the “culturing” mission of the institution. But Chicago, like Harvard, Columbia, etc. are first known as “research universities”—not as advanced vocational school providing the “skills” Business or Government imagine future workers might need.

Journalists now ask new presidents to require universities to be guided by business people to offer vocational training! The evolution may have started in the mid-20th century when, through the G.I. Bill for example, college attendance became a mass event aided and abated by Government. Until then, one mostly got into adult careers through forms of apprenticeships in the various professions and vocations. But, little by little, a college degree became the essential key for entry—though the curricula that lead to a college degree did not necessarily change, nor the people who were teaching it. Not surprisingly, starting the 1960s students who had entered college for a career started to rebel. “Relevance” became a rallying cry. Half-a-century later, it is Business that has been complaining to Government about the failures of colleges to produce workers with necessary “skills” and Government (through accreditating agencies in the United States) is drafting regulation that School might not be able to escape.

What we need to ask is why should colleges be given the task of producing workers? Is there any evidence that they are good at it? Why shouldn’t Business be asked to provide the training that it may be best at imagining is needed?