From Arts (practical), to Life (psychological), to Education (social) in the attempts to understand and analyze, in order to educate about, perennial concerns with the settings in which men, women, and children meet most intimately and extensively over the course of their lives—in a word “in families.” For a new re-integration.

This post was triggered by my hearing that the administration of the College is considering closing the Center on the Family as Educator. The creation of this Center was, as I see it, one of Lawrence Cremin’s signal academic achievements, I was moved to wonder wherefrom what moved much of my career at TC came from, dialogically. I may transform this into a fuller article.

In 1972, I joined the College into the Department of Home and Family Life, later to become the Department of Family and Community Education. I published much on matters of family and education. I did not necessarily think much about what was sustaining these concerns, institutionally. And so, now, I wonder what TC has been doing with “family” over the past century since it appears it has done much, or little. I wonder what has been included, or indexed. And I wonder whether it should continue to do something about “it” and, if so, what now. This question is partially historical, and partially programmatic.

In my beginning (Fall 1972):

My first introduction to the informal history of Teachers College came when I was shown the closet within which, I was told, were kept the teaching tools of what I did not yet know as “the Table Service Lab.” This closet contained a full set of china and silverware that, by all evidence had not been used for many decades. The department I was joining, “Home and Family Life,” for a reason I did not immediately understand, was the inheritors by default of this closet and its content.  I was also shown, and often used, the “Tudor Room” which, I was also told at some point was a copy of Miss Grace Dodge’s dining room. I was delighted when, decades later, I found out that this Tudor Room had been the Table Service Lab!

I was also shown, and often used, the “Tudor Room” which, I was also told at some point was a copy of Miss Grace Dodge’s dining room. I was delighted when, decades later, I found out that this Tudor Room had been the Table Service Lab!

In TC’s beginning(s) (1880, 1884, 1889):

Once upon a time, in those days (1880), some philanthropists in New York, led by Miss Grace Dodge, created the “Kitchen Garden Association” for the “promotion of the domestic industrial arts among the laboring classes … the better to qualify them for domestic service” (Russell 1937: 4-5). Four years later this became the “Industrial Education Association” “to include ‘special training of both sexes in any of those industries which affect house and home directly or indirectely’” (Russell 1937: 9). And then, in 1889, the same principals “incorporated” a subsequent institution “under the name of Teachers College” (Russell 1937: 7). All versions of the history of this institution emphasize the shift to the education of teachers as the best route to helping the “laboring classes” (and particularly the arriving crowds from the poorest, most rural parts of Europe) succeed (survive?) in the United States. Much of the details in this post come from the Cremin, Shannon and Townsend history of Teachers College (1954) but this history does not go in much details about what must have extended and difficult conversations.

Histories of TC then most often jump to Dewey writing about “democracy and education” (in a book that should have been titled Democracy and Public Schooling), to Dewey’s debate with Thorndike, to difficult conversations with Columbia University, etc.

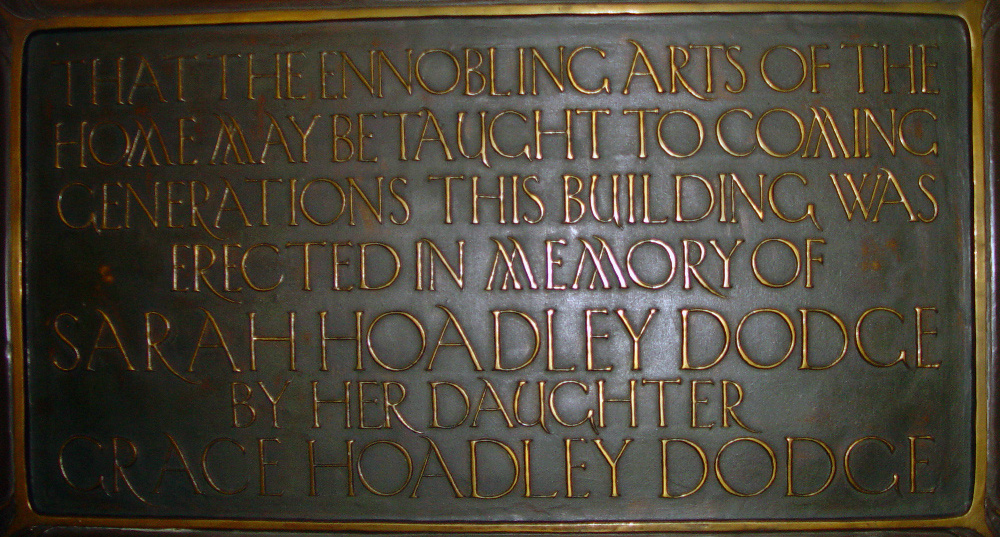

What becomes veiled in these accounts is the fact that some early concerns had not been discarded. It is significant that, among of the first buildings at the Morningside Campus were the building for the Industrial Arts (Macy), and, my focus here, Grace Dodge Hall erected so “that the ennobling arts of the home [would be] taught to coming generations” (from the plaque in the entrance to the building).  What is also often veiled is the continued inclusion in the curriculum of matters related to these “ennobling arts.” As late as 1935, the TC catalogue listed in its fields of specialization “Household Arts and Household Arts Education” with courses in “Household economics,” “Cookery,” “Clothing,” “Teaching of Home Economics in schools.”

What is also often veiled is the continued inclusion in the curriculum of matters related to these “ennobling arts.” As late as 1935, the TC catalogue listed in its fields of specialization “Household Arts and Household Arts Education” with courses in “Household economics,” “Cookery,” “Clothing,” “Teaching of Home Economics in schools.”

By 1937 the list of courses included courses in nutrition, health, child development and, most significantly given future history, a course in “family social relations.” Some of these were offered through different departments even as the old department was reorganized into a department of “Home Economics.” This department brought together most of the earlier matters but developed what became its full focus: psychological development and emotional life within a nuclear family. This transformation could probably be traced directly to the concomitant development of both Freudian therapeutic psychology (in its many transformations), and concerns with child development—as well as sociology. Ernest Osborne, who had earned a Ph.D. in Educational Psychology, was appointed in the Department of Curriculum and Teaching in the specialization in early childhood education. He started teaching a course in the “Psychology of Family Relations” (still taught as “Dynamics of Family Interaction”), and then became the prime mover of the new version of the venerable department which became, by 1953, the “Department of Home and Family Life” (Hey 1965: 134-5) . As Osborne put it in 1939:

It was once believed that parent education was a relatively simple thing limited to the instruction of parents in the proper ways of feeding, clothing, and training children . … Today .. . an increasing realization of the effects of relationship between family members on behavior is evident. (Quoted in Hay 1965: 134)

Over in Harvard, Talcott Parsons wrote a soon to become extremely controversial article on the family where women were to hold the “expressive role” in order to socialize children and stabilize adult personalities (1955: 16). Teachers College was again at the cutting edge in the transformation of an academic consensus into an educational program to apply this knowledge.

And then, as more time passed and Teachers College became my world:

I am not exactly sure what happened in the mid-1960s. I was told in my first years at TC, that, after Osborne died, the faculty of the programs in clinical psychology took umbrage at a program which appeared to give doctorate to people who would then engage in (family) therapy away from their own controls. At the same time, Lawrence Cremin got convinced that, as he put it, “education proceeds from many institutions” and particularly from families. He recruited Hope Leichter, a sociologist from the Harvard Department of Social Relations, whom he promoted, made chair of what was still “Home and Family Life” with the goal of transforming it into a department of “Family and Community Education.” This transformation was completed in 1976. Paul Vahanian, the last professor with a family therapy background, was not replaced when he retired. Rather, Leichter, Cremin and the others concerned with the matter invited anthropologists to join the evolving department (me from Chicago, and Ray McDermott from Stanford).

And then, in 1990, Teachers College, that is its administration on the basis of a recommendation by a faculty committee, closed the department and the faculty scattered.

I tell this story to make a point that keeps being obscured or, at best, side-lined: some at Teachers College always insisted that a school of education must pay attention to whatever one might want to call the institutions that take care of children when the children are not in school, or are the resting places of adults when they leave their salaried jobs.

A few at TC, I am sure, may still be willing to argue for what may have moved Grace Dodge even as she accepted that the institution she was fostering would focus on school teaching. It remains that, even in the 21st century, educators should not ignore the people who prepare the children for school, pick them up in the afternoon, clothe them, feed them, put them to bed, manage their health, and control, or not, what they read, what they watch, what they have access to in the social media of their times, etc. There is no point in rehearsing tired controversies about defining “family,” “home,” the “domestic,” etc. The reality is that, after two centuries of reformers proposing a world where children would be raised by the State, none of these utopias have survived long. Everywhere, children escape the State and yet, since the Coleman report at least (1966), and fully confirmed since, their familial experiences can challenge the State. One cannot understand “systemic privilege” without understanding the educative work of families, including their work educating themselves about schooling. This has been one of Ed Gordon (Varenne, Gordon and Lin 2009; Lin, Gordon and Varenne 2010) major contributions as he has been asking us to pay attention to what he has called “supplementary education.” It remains essential that it not be ignored.

In (temporary) conclusion, I wonder: how might we now integrate what is most easily told as a linear history: the joint concerns with the Arts of the domestic (economics, ecology, sustainability), Life with the most significant others (emotions, disabilities, cognition, development), and Education about all this (privilege, resistance, imagination).

Coleman, James et al. 1966 Equality of educational opportunity. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. (with et al.)

Cremin, Lawrence 1974 “The family as educator: Some comments on the recent historiography.” Teachers College Record 76, 2: 250-265.

Cremin, Lawrence, David Shannon, and Mary Townsend 1954 A history of Teachers College, Columbia University. Columbia University Press.

Hey, Richard 1965 “Ernest G. Osborne Family Life Educator.” Journal of Marriage and Family , 27, 2: 134-138.

Lin, Linda, Hervé Varenne, and Edmund Gordon, eds. 2010 Educating Comprehensively: Varieties of Educational Experiences. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press,

Osborne, Ernest 1939 “Widening Horizons in Parent Education,” Teachers College Record, 41 p, 28.

Parsons, Talcott 1955 Family, socialization and interaction process. Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press.

Russell, James 1937 Founding Teachers College. Bureau of Publications: Teachers College, Columbia University

Varenne, Hervé, Edmund Gordon and Linda Lin, eds. 2009 Theoretical Perspectives on Comprehensive Education: The Way Forward. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Print This Post

Print This Post