In this post, I am doing something somewhat different from the usual. I am maintaining the order I think I have established (at least as I look at it, retrospectively): this is an experiment in anthropological theorizing and teaching. But I am delving further into parts of my life that I have not brought out.

So here it goes: applied medical anthropology

A few years ago, my wife, Susan, was diagnosed with a form of cancer known as “myelofibrosis” (who may not know it under that name might be a topic for another post as the exact name can be consequential—see below). The “official” diagnosis was made, not surprisingly by an oncologist, the acknowledged, state approved, expert who can transform speech (this is myelofibrosis) into not simply an act, but a sequence of new moves a particular set of others, from the patient, to her family, to insurance companies, must now make. [This would be easy to model as a special case of entry into a particular kind of polity of practice.]

The oncologist told us, as I remember it four years later, something like: “People live with this for 15 years or more … You are likely to die of something else … It will change your everyday life as you will now have to schedule regular medical visits.” I remember she was altogether good at telling us something that we knew, and much that we did not know: we had certainly never heard of this cancer or of its treatment. Of course we went to the Internet and learned what we could, talked to her further, and settled into what I am experimenting in calling, for various theoretical reasons, a “new normal.” Actually, what we learned was not extremely bad news for people entering in their 70s. The oncologist then (and I will keep emphasizing conversational and interactional temporality) tried a drug that would alleviate the symptoms of a cancer that affects the production by the bone marrow of red blood cells: profound anemia and the attendants limits on mobility.

Susan’s body, in its thinginess and peculiarities, was leading us to various particular disabilities that can be mitigated or expanded depending (de Wolfe 2014).

So, this was actually a good time for us to adopt the car culture of suburbia. The long walks in Manhattan to which we were accustomed would not have been possible anymore. We escaped one disability.

Things were relatively stable for a few years. We had educated ourselves in still another polity of practice. We evolved a new adaptation to the now extent conditions given our resources and consociates. This was now our new normal, the culture we could not quite escape (though we tried some bricolage with it).

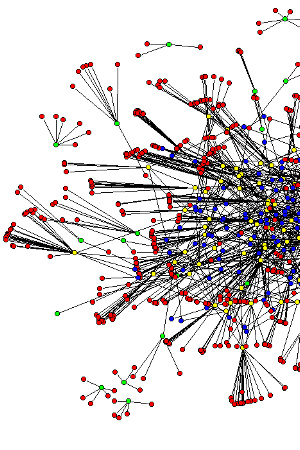

At that point I would have described our “actor-network” as consisting of:

- a general practitioner

- a clinic with a staff of

- oncologists

nurses

secretaries

- a mail order pharmacy

- a radiology center

That is, ethnographically, these were the people with whom we had to talk in order to maintain the syntagmatic order of the treatment. Each of the person (but not any) could authoritatively tell us when to show up for an appointment, what tests or drugs to take and when. This question could be asked here but not there. This act could be performed here but not there, before but not after this other act, etc. [one should also be able to model this syntagm.]

At that point further actor nodes in the network remained as faint indexes mostly buried in the conversations with the interlocutors we mostly had to address. We did receive reports from the insurance company about what it was paying the doctors, how much it reimbursed for tests and drugs. While reading these we were amazed (guilty? thankful for the opportunity?) at the cost of the primary drug: $1,600 a shot, every six weeks.

But cost and attendant controls was not part of the syntagmatic order of the treatment as we experienced it so far.

And then something happened.

In my other life, as long-term employee of Teachers College, I know that insurance companies are big players in constraining what we can do. Every few years, we are told of long conversations TC has with the various major companies. We are told about the final proposals and why TC might shift, as it did starting in January 2015, from United Health Care to Aetna. The cost of these conversations are barely indexed though I have a good sense that it is not trivial, either from TC or the companies: staff time and compensation, consultants, lawyers, writers of glossy presentations, etc.

Anyway, the shift by my “employer” (the term is consequential here) brought to my practical attention the insurance company as we registered on new web sites, a new mail-order pharmacy, new styles of reports, and we continually checked and re-checked that the various doctors that were part of my wife’s actor-network were also “in network” (consequential category in American insurance).

I thought this would only be a minor annoyance and that we would return to the “old” (2014) new normal.

This was not to be.

Aetna told us (clinic, oncologists, Susan and I) that the drug, Aranesp, that had worked at maintaining Susan’s condition for three years was:

a) experimental for her disease

b) experimental drugs were not covered by Aetna’s contract with “the employer”

Aetna told us, emphatically, repeatedly, after a variety of appeals by various actors, “NO MORE PAYMENT FOR THIS!” Through this speech act Aetna revealed itself as an inescapable interlocutor in the ongoing conversation. The expanded text of Aetna’s statement repeatedly indexed two different other worlds:

a) it challenged, successfully, medical practical authority (Aetna did not attack its legitimacy but its everyday consequentiality: what is not reimbursed will not be used)

b) it challenge me to, perhaps, challenge TC about a not so minor detail in the contract it has signed with Aetna (and may or may not have allowed it to undercut United Health Care)

I will not go through the many conversational turns that led, after three anxious weeks to Susan starting a new, and altogether experimental treatment (since we will not know for several months whether it will work) at the (reimbursed after full consultation and authorization) cost of … $11,000 a month (not to mention added visits to the oncologist, more costly tests, a blood transfusion)!!! (I cannot help but believe that Aetna, as a monstrous network of actors with conflicting authority, confused itself: the outcome is altogether … surprising!)

Who knows that Aetna may be correct in its act and is practicing medicine better than our oncologist (though Aetna is careful, I think, never to shapes its speech as an instruction to “do that”). But, for now, here is our expanded actor-network of consociates who make a difference:

- [the one listed above is still very much active]

- various parts of Aetna:

- the doctor(s) who categorized Aranesp as “experimental-for-this-purpose” and the other doctors who discussed our oncologist’s recommendation (she told us how one of them told her to not get so involved in the case! She was not happy!)

- the staff members of the clinic who have to check the why’s and wherefore’s of each step, repeatedly, with the staff member of Aetna. The number of phone calls, waits on hold, recalls, faxes, etc. is astonishing.

- Susan multiple calls to clinic, hospital, Aetna special pharmacy.

- various parts of Teachers College

There are many anthropological points but, to emphasize my usual themes:

- these are not matters of social structure (à la Parsons) or modern governmentality (à la Foucault) nor even neo-liberalism. There are matters of structuring through interlocking conversations that transform the field even as they seek the production of temporary (immortal) new normals.

- in these conversations everyone “screws around” (Garfinkel) even as they all play deeply with matters of life and death (Varenne & Cotter ).

- ethnomethodology, conversational analysis, and actor-network-theory (that expands on the other fields) are the most useful starting framework but they are not sufficient

- screwing around and playing deeply will always produce something extra-vagant (Boon ) that is not predictable on the basis of efficient rationality.

- each moment in the evolution of the normal-for-some-now (“culture”) makes sense as a syntagm in a local order. But this syntagm is always at the edge of catastrophic collapse that leads, in temporality, to

A) instructions “do NOT screw around! Stay in line! Do what your doctor tells you to do”

B) efforts to bricolage one’s way out of the order and thus:

THIS POST

References

de Wolfe, Juliette 2014 Parents of children with autism: An ethnography. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Varenne, Hervé and Mimi Cotter 2006

“Dr. Mom? Conversational Play and the Submergence of Professional Status in Childbirth.” Human Studies 29:41668.

[here is the list of the most common references I use. Many of these are implicitly indexed in this post]

Print This Post

Print This Post