(Nimuendajû 1942: 17)

Last week, I heard a most interesting paper by Oren Pizmony-Levy and Gita Steiner-Khamsi about, of all things, school reform in Denmark! It may seem strange that I resonated to such a topic.[Ftn 1] But it should not appear so: in graduate school, I also resonated to reading ethnographies of Ge people of Central Brazil! People over all the world do amazing things and “school reform” is one of them.

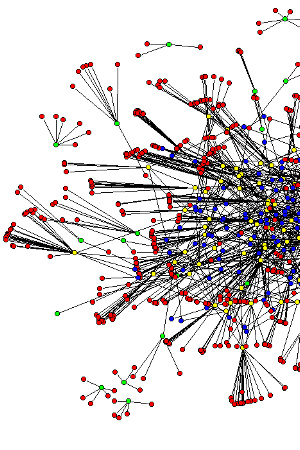

an example of the representation of a network

using UCINET (White 1997)

Last week, I particularly resonated to the methodology. Nimuendajû, the great ethnographer of the Ge, in his time, modeled Šerente villages on the basis of his local observations. Pizmony-Levy and Steiner-Khamsi have found a way to make visible networks involved in the production of “school reform,”[Ftn 2] on the way I suspect to modeling how such reforms proceed. Their work is part of a broad movement in the social sciences, and anthropology in particular (at least in the networks who attempt to build on Jean Lave’s work as transforming social structural analyses). The goal is to trace movement and change (or return to the old normal) in position, and perhaps even in the field of positions within which people move (including school organization). The current consensus, backed by much ethnography, is that these changes do not “just happen” as effect following some cause. It proceeds through deliberate action by emergent polities. Nimuendajû did not have the tools needed to trace how the Šerente came to do something that could be modeled as he did. But these tools are now available.

More on this another time.

What surprised in me most Oren Pizmony-Levy and Gita Steiner-Khamsi’s paper was that the most quoted document in the network of people and institutions who performed “school reform” in Denmark was …. an ethnography, of a school, by Danish anthropologists!

Anthropology of education, actually applied for what appears positive change!

Continue reading “On the (mis-)use of anthropology”