This is the third in a series of notes to fifteen lectures for my class Communication and Culture.

Required Reading:

- Fiske, John Understanding popular culture. Boston: Unwin Hyman. 1989. (Chapters 1, 2, 3, 5, 6)

| Transition notes |

|---|

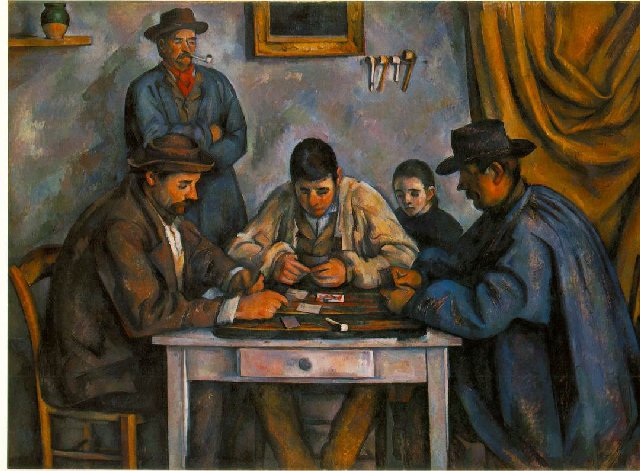

Cézanne and the space (field) of "culture" : a paradigm of uses constituting a field (beyond definitions)

Cézanne and the space (field) of "culture" : a paradigm of uses constituting a field (beyond definitions)

|

- From made-up diversity to (high/popular/hegemonic) culture

-

Given a concern with unavoidable diversity in the ways human beings appear to each

other, and a concern not to reduce this diversity to universality prematurely, then it

makes sense to wonder about

- where diversity comes from (causes and history; evolution? chance? necessity?)

- the products of diversity (culture as product and objects --> "cultureS")

- the activities that diversify human groups (culture as process -->"Culture")

- the impact of group diversity on participating persons (enculturation and the construction of the self)

Cultural anthropologists have above all been interested in the causes of human diversity (fighting racism, mechanism to emphasize the multiplicity of solutions human beings have given to similar conditions), and many have also been interested in the impact of "cultural" diversity on persons.

With some exceptions (LÚvi-Strauss arguably being one, and Marx and some Marxists depending on where the emphasis is put in their work), it is only relatively recently that much work has been done emphasizing the processes that makes differences given an apparently homogeneous and coherent starting point. An early figure with a profound influence is that of the Russian Mikhail Bakhtin whom we will discuss later. Many of those have established the importance of "popular" culture in understanding how human beings make up their world.

- In many ways, the concern with "popular" culture (by contrast to "high" culture) is a paradoxical return to the universalistic concerns of the early philosophers of culture: to be concerned with popular culture is to be concerned with the productive aspect of humanity. It is to be concerned by ALL that human beings do, whatever it may be and whereever it may take place.

-

But what exactly does this mean? Alternatively to be concerned with humanity is to

be concerned:

- individual human beings, their constitution and characteristics (the "pragmatist" orientation);

- what human beings have done and how it now constrains if not determine them (a "sociological" orientation with both Marxist and Durkheimian versions);

- what human beings are doing with each other and with what other human beings did in the past (the orientation to "resistance" and "popular" culture);

-

This might also be presented as an evolution in the conversations about culture from

- a concern with consensus (learning);

to

- a concern with social structure (and determination);

to

- a concern with continuing productivity (resistance);

OR from a concern with

- culture as history imposing itself on individuals;

to

- culture as the activity of individuals in history;

-

Given a concern with unavoidable diversity in the ways human beings appear to each

other, and a concern not to reduce this diversity to universality prematurely, then it

makes sense to wonder about

- The problematics of the popular

-

The latter summarizes the import of Fiske's argument in Understanding popular

culture. Note that this is not an opening to research into the characteristics of

the individuals (the social psychological common sense that takes us back to sociological

determination) but rather to a confrontation with the "freedom" or at least

ultimate indeterminacy of practical human action in historical conditions.

Fiske makes his argument through a set of oppositions between

popular culture

producerly text

jouissance (carnival)

(progressive politics

vs.

vs.

vs.

vs.

hegemonic culture

writerly text

pleasure (discipline)

conservative politics)[Note that Fiske has a tendency to reify "popular culture" by writing as if it were an "it" with characteristics (e.g. p.43 "there can be no popular dominant culture"; p. 103 "A popular text should be producerly"; and passim). More consistent with the approach would statements to the extent that no culture can be so dominant as to prevent people from using it "popularly."]

-

The central focus here is on the continuing production of every day life and

on the relative freedom of people in the conduct of their everyday life to interpret that

which they encounter or consume. The central concept is that of "appropriation"

for particular purposes often not envisioned by the original "writers" of the

texts.

The emphasis is on the making of difference rather than on the movement towards consensus. This is a principle of all humanity.

This statement is an inductively developed theoretical one with major deductive implications. Given the premisse outlined above, it must be the case that ALL human beings are involved in "making a difference," and this must include Ronal Reagan as President of the United States as well as Australian aborigines in the bush as the watch Rambo (to use the example to which Fiske repeatedly returns, pp, 57, 136-37, 163, 168).

- One should also wonder about the ability of texts to control their readings. Fiske emphasizes that no text can do so absolutely. The reverse should also be emphasized: the appropriation must be demonstratably coherent to something in the text. Thus one can wonder what, in Rambo, allows for a aboriginal reading, and then wonder back about what people like Ronald Reagan do with similar passages.

- the "text" (movie, video, technology, painting, etc.) as object produced by a process (commercial, political)

that takes us to issues of (hegemonic) power through semiosis (the use of arbitrary signs) but also as "dead"

until picked up for "interpretation" by the indefinitely large number of audiences that might pick the object

for their own local productions. Thus Rambo

- is a product of Hollywood (and American, capitalistic hegemony) attempting to control the world through the manipulation of male machismo

- allows for a classic critique of American government in the name of local American democracy (Jefferson, against Washington)

- as well as an occasion of cultural production and possibly transformation of America (or Pakistan...)

- the relationship of the popular to the imagination of current events.

- Making one's own music in church: the history , suppression and "rediscovery," of "shape notes"

(also known as "Sacred Harp") in America.

- Dreaming about the (whichever) war (on love and death: pathos, exploitation, or political critique?)

- On Coca-Cola, singing in harmony, and world peace (and Teachers College?): back and forth on commerce, the popular

(and the philosophically hegemonic?)

- Making one's own music in church: the history , suppression and "rediscovery," of "shape notes"

(also known as "Sacred Harp") in America.

-

The latter summarizes the import of Fiske's argument in Understanding popular

culture. Note that this is not an opening to research into the characteristics of

the individuals (the social psychological common sense that takes us back to sociological

determination) but rather to a confrontation with the "freedom" or at least

ultimate indeterminacy of practical human action in historical conditions.

| Some questions |

|