This is the fourth in a series of notes to

fifteen lectures for my class ITSF5001:

Ethnography and Participant Observation.

Table of contents of the lecture

Ethnography as work: what do ethnographers do and where do they do it?

Ethnography as work: what do ethnographers do and where do they do it?

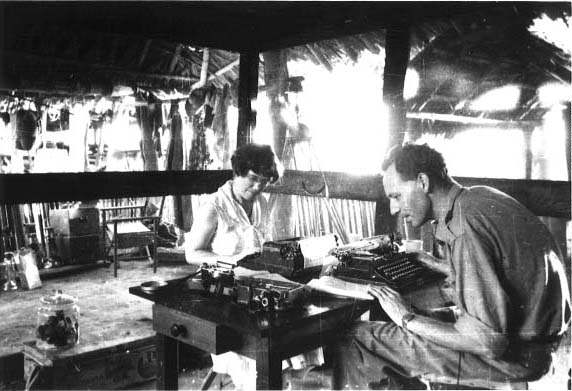

- The simple answer is that they write, and that they do that in whatever temporary home they go:

- Thus the importance of preparing one's principal work site

- Nowadays. most anthropologists write on their computers and they must deal with new issues:

- File organization (naming conventions, organization of different types of field records, etc.)

- File backup: MOST IMPORTANT

- File protection (passord, encryption)

- File retrieval

- Nowadays. most anthropologists write on their computers and they must deal with new issues:

- and, over the time of one's research, determine what tools to use.

- NVivo and other "qualitative" research softward

- rolling one's own through using various features of Word or other all purpose software

- video and sound software

- Thus the importance of determining, through trial, error, and approximation, what and how one will "write."

- Thus the importance of preparing one's principal work site

- The complex answer involves a constant recalibration of how one is (participant) observing and how one is recording, first, during the observation, and most importantly, later, during the writing stage.

- The simple answer is that they write, and that they do that in whatever temporary home they go:

- What do ethnographers use? (a technical question)

The more practical answer to the main question starts with a brief review of possible modes of observation:

- One on one:

- The structured interview

- short-range with a set of pre-written questions;

- long-range:

- longitudinal

- life-history

- The unstructured interview (with a generalized set of questions opening the interview)

- The conversation (starting with a general topic)

- etc.

- The structured interview

- One on some:

- Focus groups (tightly run by a leader)

- unfocused groups

- Conversations (with minimal leadership besides the setting up of the conversation)

- Participant-observation (at occasions set up by the people observed, e.g. a dinner party)

- etc.

- One on many:

- Observation with some active participation (e.g. asking clarification questions from a participant during a parade)

- Observation with little active participation

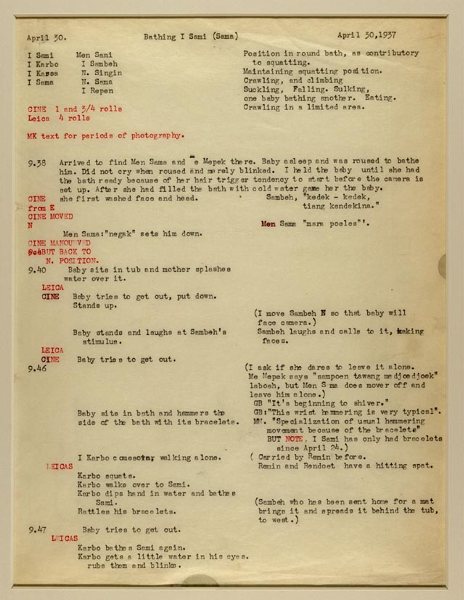

- Observation through mechanical means (photographs, audio and video tape)

- Collection of artifacts

- etc.

- One on one:

-

Inevitably: "fieldnotes" -- that is "texts from the field"

Types

Types

We can now review the classificatory scheme from Sanjek (1990). I have added a few more to approximate how one might approach Malinowski's list of what one should come back with from the field.

- Head notes

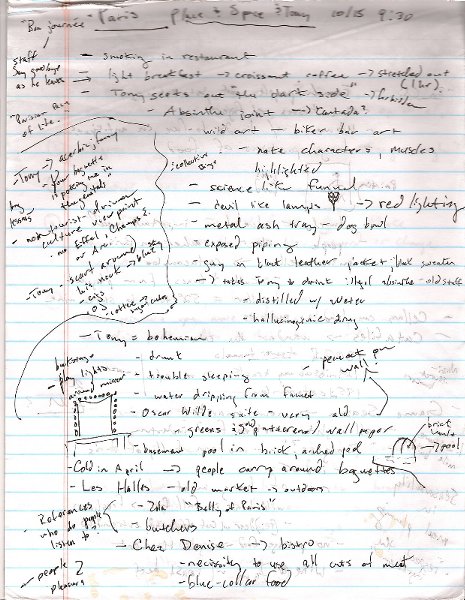

- Scratch notes

- Rewritten field notes on the basis of the scratch notes.

- Fieldnotes Proper

- Journals and Diaries

- Field Records

- Texts

- Maps, photographs, video clips

- Letters, Reports, Papers

- Tape transcripts

- Questions of "Quality"

- Note that, in every case, the issue concerns WRITING what there is to OBSERVE (i.e. the "stuff that happens," the (experience of the) phenomenon. Thus, by definition, all the classical philosophical strictures about the relationship between language and the world apply. (see Merleau-Ponty on The prose of the world (1973 [1969]). Thus the extent to which fieldnotes represent the phenomenon (a phenomenon) must be problematic.

- Given an understanding that, at best, field notes are maps of a territory, rather than the territory itself, it is the responsibility of the fieldworker to specify what are the features that were picked up for writing (and indicate an awarenesss of the features that were not picked up--for the discussion of the specific limitation of a particular ethnographic research). This should help establish that you have observed what you said you would observe.

- Given the further understanding that the main rationale for ethnographic

research lies in the awareness that the definitions (conceptual

boundaries) of a phenomenon-to-be-researched are potentially problematic,

it is also the responsibility of the fieldworker to indicate whether

the writing allows for an investigation of the boundaries.

-

Writing for (vs. observation of)

- The act of writing fieldnotes (and later of writing an ethnographic report) has often been compared to translation (moving meaning from one signifying system to another) and, less often, to transcription (rewriting from one medium to another, that is from text to text).

- It would be better to think of writing fieldnotes as in-scription that is of making text out of something that is not textual in the same manner. In this sense any form of measurement is inscription, as are all maps, models, etc. When this is understood, then it is clear that the critique of scientific activity that point out that all observations are "made up," that is that facts are, precisely, "facted" rather than given (gathered, etc.), is not a radical critique of the possibility of science but rather leads to a more precise delineation of the responsibility of the researcher to trace how and why he has made up what he has made up.

[fieldnotes by Portia Sabin on this lecture as given on October 10, 2000]

[the Irish site: notes, interviews, photographs, documents]