This semester I had the good fortune to accept a request from a student: “Could we have a seminar on play?” So, first, thanks to Miranda Hansen-Hunt, Andrew Wortham, Michelle Zhang.

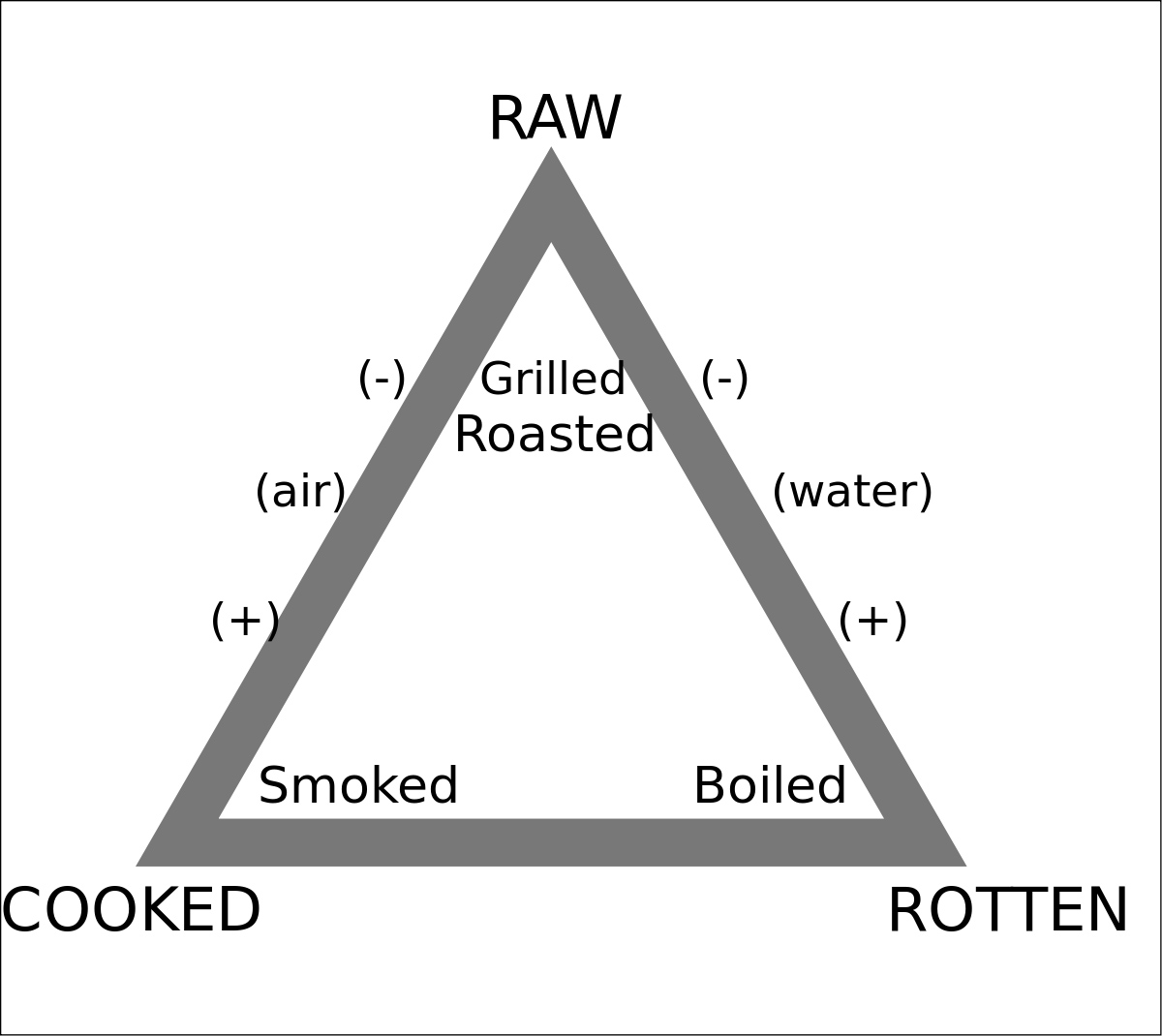

We started with the obvious: Bateson on “this is play” (1955), Geertz (1973) on “deep play,” Boon on “extra-vagance” (1999), Bakhtin on Rabelais ([1936] 1983), Garfinkel on trust (1963). One thing became salient as we proceeded: each of these authors start with accounts of public displays, without the attending interviews that too much anthropology now comes to rely upon. Some of the authors write in terms of psychological states (having fun, learning, trusting) but they do not investigate the states as such. Rather, and however abstract the argument, they work off anecdotes more or less grounded in ethnographic or historical accounts. So we are asked to imagine:

• puppies roughing it

• men betting to the point of threatening their status (or climbing extremely dangerous mountains)

• men and women parading as kings and queens during a festival while every one is laughing.

• people responding to certain moves in tic-tac-toe

All this is great fun for a cultural anthropologist altogether optimistic about humanity. But it left this anthropologist, as the seminar ended, with the question: when is “this is serious”?

• when is a bite NOT a play bite?

• when in climbing a mountain NOT an extreme sport?

• when IS a king?

• when is a game of tic-tac-toe (greeting, explanation,…) played seriously?

Or, more precisely, when would an anthropologist recognize that this is not a game, that “this is NOT play”? What are the performative markers than might confirm to an observer that this is serious?

It ought to be well known that the anthropological thread that Bateson activated started with his noticing how interesting it should be, for general communication theory, that, when puppies bite each other, only some bites are followed, sequentially (temporally), by NOT play behaviors. Bateson assumed that his readers had seen dogs fighting and could tell the difference. He was trusting on some routine common sense. There actually is an ethnographic literature on insults that document the always possible shifts from laughter after a particularly well crafted insult to snarls if not fists, knives or guns (Labov 1972, 1974). Bourdieu’s writing on the practice of honor in Algeria also fits here (1966). One can start a climb up Mount Everest as a sportsman, as paid Sherpa, or as a professional saving a sportsman or Sherpa in mortal danger (Ortner 1999). There is deep play and NOT deep play—though both can end in death.

The fundamental question in all sociologies, as Garfinkel pointed out in the “trust” paper, is not so much order and systematicity as “the phenomena of ‘alienation,’ ‘anomie,’ ‘deviance,’” (1963: 237). As it might be put, playfully:

We can all recognize that a duchess might be as disappointed at a failure to receive an invitation to have tea with the queen as a chimney sweep might be at losing an opportunity to be the queen’s sweep. (Moore & Anderson 1963: 186)

The recent concerns with tensions over race, gender, etc., are versions of the same concern with all activities that maintain and challenge order including what may “just” be playful carnival (that ends at midnight) or dangerous riot (that never quite ends but is sometimes followed by violent repression if not revolution). If anthropology is to be sensitive to the travails of human beings, how can anthropologists tell whether this performance is fun or hurtful, an extravagant hyperbolic performance or a deeply hurtful insult?

Let’s stay with the disappointed duchess and the queen. We have two human beings tightly linked in an asymmetrical relationship. And we have information about the psychological state of one of them. The link is constituted, on a day to day basis, by a series of rules that may be specified with even more details than the rules for chess and might still miss much that will remain unspecified until controversy arises (the “etc. principle”). Yet, any actual performance of the relationship, in a routine temporal sequence of statements/actions (“speech acts” such as “I invite you tea”), is, at crucial moments, dependent on the trust that neither duchess nor queen will play the game wrong when “playing the game wrong” is actually a common move in the relationship even as calling out “this is a wrong move” is itself a powerful and dangerous move that either closes an argument, or escalates it.

What makes all this serious is not only the status that may be at stake among the key participants, but the status of many more people: the duchess/queen/tea/disappointment package is actually a package assembling a crowd of people (in the court, among the servants), a crowd of possible events (dinners, balls, hunts, etc., and also marriages, career advancement, etc.), a crowd of motivations and other psychological statements (including satisfaction among some at the duchess’ disappointment…). This mess of an assemblage working practically at accountable and enforceable division (Hetherington and Rolland 1997; Gershon 2012) is not, by almost any definition, a “community.” But it can be referred a “polity.”

As I see it today (and all this will have to be developed), what makes this serious is it’s placing in a temporal sequence that is not, in any simple way, a frame. By contrast, even the most dangerous of deep plays are framed with marked beginnings and ends, with statement such as “I will climb Everest this summer” followed later with “I climbed Everest last summer.” The best detailed ethnographic account of such a sequence may be Sacks’ “joke’s telling” paper (1974). By contrast (not) being invited to tea or, for that matter, (not) being asked to tell a joke, or play a game, may not have a clearly marked starting point and may never quite end, perhaps even after the people have died depending on the stakes involved in the (not) being asked.

So, let’s say that a duchess/queen/tea/disappointment package is NOT play, not a game, nor a play on a stage with specifiable rules, personae and roles (chess pieces). It is not NOT play because it is alive so that the unfolding of the event may actually change the rules, the personae, the roles. Consider how the package made sense, in the France of the first half of 1789, and did not make sense anymore four years later when the queen did lose her head, literally.

I have recently been writing about cultural arbitrariness necessarily raising the kind of practical consciousness that leads to culture change. Consider the ongoing struggles around the rules for gender markers: what are, now, the taken-for-granted, unconscious, routine, “rules” as they might be written by a visiting anthropologist from Mars? I would now add that what Saussure, Bourdieu, and I, refer to as “arbitrariness” is directly related to the “etc.” principle. The speech act “it’s turtles all the way down,” in practice, is a challenge to a challenge (colonial subject irritated at colonialist condescension). “Yada yada” is not only a call to common sense (“you know what I mean!, Right?). It is also a warning: this play insult may become serious if you continue. All this is inevitable because of the very affordances of any symbolic system: it cannot handle all possibilities for experience is always richer and evolving, thereby leaving everyone with serious problems.

A final comment on the unruly properties of specified rules when things are NOT play. When doing fieldwork in a New Jersey high school, I had to insist to see the book of “rules and bylaws” (Varenne 1983: Chapter 8) It was gathering dust high on a filing cabinet in the principal’s office and he wondered why on earth I might be interested. As he put it “most of the rules have never been written down.” This was the case. There were pages of rules about this or that that were no more than titles. But, when things got serious, perhaps because the principal was trying to find a way to fire a teacher, then a rule might be written down, perhaps even after the event. Writing a rule after an event, and then invoking it, is, of course, inappropriate: there are rules about rules about rules (all the way up?).

NOT play does not have rules. It is about making rules, and then not following them whether for resistance or the assertion of power. This is serious.

References

Bateson, Gregory 1955 “The message ‘This is play’.” in Group processes: Transactions of the second conference. Edited by B. Schaffner. New York: Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation. pp. 145-242.

Bakhtin, Mikhail [1936] 1983 Rabelais and his world. Tr. by H. Iswolsky.. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press.

Boon, James 1999 Verging on extra-Vagance: Anthropology, history, religion, literature, arts … showbiz. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre 1966 “The sentiment of honour in Kabyle society.” in Honour and shame. Edited by J.G. Peristiany. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 193-241.

Garfinkel, Harold 1963 “A conception of, and experiments with, ‘trust’ as a condition of stable concerted actions.” in Motivation and social interaction. Edited by O.J. Harvey. New York: The Ronald Press. pp. 187-238.

Geertz, Clifford 1973 “Deep play: Notes on the Balinese cockfight.” in his The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books. pp. 412-453.

Gershon, Ilana 2012 No family is an island: Cultural expertise among Samoans in diaspora. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Kevin Hetherington and Rolland Munro, eds.. 2014 Ideas of difference : social spaces and the labour of division. Oxford ; Malden, MA : Blackwell Publishers/The Sociological Review

Labov, William 1972 “Rules for ritual insults” in Studies in social interaction. Edited by D. Sudnow. New York: The Free Press. pp. 120-169.

Labov, William 1974 “The art of sounding and signifying” in Language and its social setting. Edited by W. Gage. Washington, D.C.: The anthropological Society of Washington. pp. 84-116.

Ortner, Sherry 1999 Life and death on Mt. Everest. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Varenne, Hervé 1983 American school language: Culturally patterned conflicts in a suburban high school. New York: Irvington Publishers.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Print This Post

Print This Post